-

America’s War for Independence James F. Murphy Jr. Chapter Four Boston’s London Bookstore was crowded but orderly. It was quiet as customers turned pages and scoured broadsides of current events of entertainment and lectures. Henry Knox, the 25-year-old proprietor, curled up on a stool near the door relishing every sentence, phrase, and illustration of the…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy I haven’t been to Grand Ave since November. For me, it’s not just a street, but a place. And 36 was more than a house or even a home; it was the seventh Murphy sibling. The last time I walked up the brick path was Monday, November 17th, 2025, the day after my…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy No one prepares you for the transition from Daddy’s Girl to Fatherless Daughter. Ten years ago, you left us on September 27. The day fell on a Sunday, and as I awoke, I found myself trapped in W.H. Auden’s poem, desperate to stop all the clocks – and the sound of…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy Back in March, three members of the Falmouth (Massachusetts) Republican Town Committee held a public meeting at Gus Canty Community Center in Falmouth about their proposed Bill H.2042 (HD. 2535), “An Act Relative To Child Protection.” The Bill seeks to remove the last line of a Massachusetts law already in place with…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy Last week, I celebrated my anniversary. My own Independence Day. The place that gave me my freedom is behind bars. Planned Parenthood in Providence, Rhode Island. The last I knew, the person who got me pregnant is also behind bars, after another armed robbery to fuel his heroin addiction. I still…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy My mother and I have lived parallel lives. She had no choice but to become a mother of a large family, and while I’ve never doubted her love for my five siblings and me, watching her be unfulfilled in that role gave me no other choice than to pursue an alternative path. …

-

By Sarah E. Murphy Falmouth joined towns and cities across America on Monday, February 17, for a peaceful protest in opposition of Donald Trump and the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), overseen by billionaire Elon Musk. The message mirrored the name of the event: We Choose To Fight. The “No Kings Day” protest was a galvanized…

-

Sarah E. Murphy My mother’s mother, Johanna Irene “Josie” Gaudet, was born on this day in 1894, in Pleasant View, Prince Edward Island, where she grew up on a farm as the second of seven children, three girls and four boys. She boarded a ship in St. Louis, PEI at age 28, by herself, emigrating from…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy When I first read about – and later heard – the ignorant, hateful “Lock her up!” chants directed at our former First Lady and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, it was eerily reminiscent of an incident I experienced in junior high. It was 1985. I was thirteen years old, a seventh-grader…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy I wrote the following poem in the fall of 1989, when I was 17, a senior in Mike Rainnie’s poetry class at Falmouth High School. Although my deserted neighborhood of Falmouth Heights in the 70s and 80s was a ghost town, Halloween was still a major event in our family. My…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy The first time I ever heard about my great-aunt Margaret Matthews, I assumed she was the namesake of my mother, Margaret Ann, the only girl in a family of three boys. “Oh no,” my mom said, when I asked her one day while staring at Margaret’s photo. “I was named for…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy Yesterday marked nine years since my father’s death. Nearly a decade since I watched from my parents’ bedroom window as the undertaker arrived to take Dad from 36 Grand Ave, and us, forever. A date I dread and feel in my bones as it approaches each year, like the sudden shift from…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy Today is September 10, which is also Suicide Awareness Day here in America. It’s something that impacts all of us, whether we address it or not, for it doesn’t discriminate. There are many people I keep close to my heart who have died by suicide, and I think of them often.…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy I received a phone call one afternoon in late Spring 2024 from a number I didn’t recognize. I was rushing to get into my car, so my first instinct was to ignore it, assuming it was probably a robo call, but there was a name on the screen, and something in…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy My earliest memories of moving from West Newton to our newly renovated summer cottage in Falmouth Heights, and the only memories I recall of having one-on-one time with my mom, date back to the mornings and afternoons she and I spent together as she first began cultivating her garden, when I was…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy I recently celebrated another year on this planet by taking a quick weekend trip to Orleans with my husband, Chris. One of the things I appreciate most about Cape Cod is that each of the fifteen towns is unique, all with different alluring and signature characteristics, like the proverbial (as opposed…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view – until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” One of Harper Lee’s most quoted lines from “To Kill a Mockingbird,” spoken by Atticus Finch to his daughter, Scout, to illustrate the importance…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy It’s hard to believe it was only 51 years ago today women “won” the right to govern their own bodies. Even harder to believe a country that prides itself on being free and brave has taken that right away. How can America possibly call itself a civilized nation when women have…

-

I wrote the following poem my sophomore year at Bridgewater State College (now University), when I was 19. I was taking a course at Boyden Hall on Tuesday nights called “Writing About Literature,” taught by a woman who was a reporter for the Taunton Daily Gazette. She was tough but fair and, like a journalist,…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy I wrote the following poem in December 1991, for my mom’s birthday, when I was a sophomore at Bridgewater State College. At 19, I was finally able to grasp why she didn’t always seem merry in the weeks leading up to the holidays during my childhood, when she was busy making…

-

I don’t allow myself the luxury of grieving. Instead I hide it like a secret pendant I wear on rare occasions. If I let myself start I’d probably never stop so I find I’ve returned to my former self the cynic who chides couples holding hands and locking lips needing to turn away. You wandered…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy I was on a train from Rome to Cinque Terre when I learned about the tragedy in Port Clyde. While scrolling online in an effort to get an answer about a situation I was dealing with back home, I couldn’t escape the headlines and corresponding photos. “Beloved Maine businesses destroyed by…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy Last Sunday, May 14, here in the United States, we celebrated Mother’s Day. As social media was flooded with posts in celebration of motherhood, all I could think about was Mary Teresa Collins, a woman with whom I recently connected on Facebook. Mary was born and grew up in Ireland, but…

-

By James F. Murphy Jr. The following article, written by my late father, was originally published in The Boston Globe Travel section on December 3, 1995. Much like Ishmael in “Moby-Dick,” I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is damp, drizzly November in my soul, I head for Ireland. Ireland? At…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy I stopped caring last year. Not about life, or living. To the contrary. I was reminded far too many times how fragile and fleeting this journey is. I stopped putting my priorities on the back burner in order to please. I stopped denying my dreams by thinking I’m not deserving. I…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy I was born in 1972, one year before Roe v. Wade, when abortion in America was illegal. I never imagined I’d spend sleepless nights at age fifty worrying about my nieces’ reproductive freedom. But then again, I never imagined I’d need an abortion. When I celebrated my milestone birthday last March,…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy It was September of 1990, my freshman year at Bridgewater State College. I was 18, and he had just turned 21. Although he was a junior, he was a year older than his BSC classmates, having graduated from New Bedford High School in ’87. He was also a commuter, who drove…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy June 27, 2022. A cool and rainy grey day. Celtic vibes on Cape Cod. My dad’s favorite. The kind he’d spend writing in his upstairs office, the bedroom Courtney and I once shared when we were small, after moving full-time from Newton to our magical Falmouth summer home. The window overlooking…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy It’s been just over a year since I stopped hiding. Since I said, and wrote, the words that have always been barely beneath the surface. I had an abortion. My decision to speak out right before the 2020 Presidential election was years in the making. Twenty-five, to be exact. A physical…

-

Text and Photos by Sarah E. Murphy While Stephen Bird was busy last week preparing his signature soup and clam chowder for the Cape Cod Marathon, he had no idea how much those efforts would be appreciated, not just by the running community, but the town of Falmouth in general. After a one-year hiatus in…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy For as long he can remember, Stephen Bird has lived a lie. Now, at age 53, he’s finally ready to speak the truth. Steve and I first connected in October 2018, when he was referred to me by our mutual friend, and my fellow Falmouth writer, Joanne Gartner, about the prospect…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy I recently stumbled on the following essay I wrote a few weeks into my first semester at Bridgewater State College (now University), in the Fall of 1990, for one of Professor Maureen Connolly’s writing classes. I don’t remember the exact assignment, but it details the day my parents drove me to…

-

Poetry and photos by Sarah E. Murphy I used to drive by religiously to make sure it was still there. Every time I rounded the Heights Hill I held my breath wondering what would greet me at the top knowing any day it could all change. And each time I saw the vista of my…

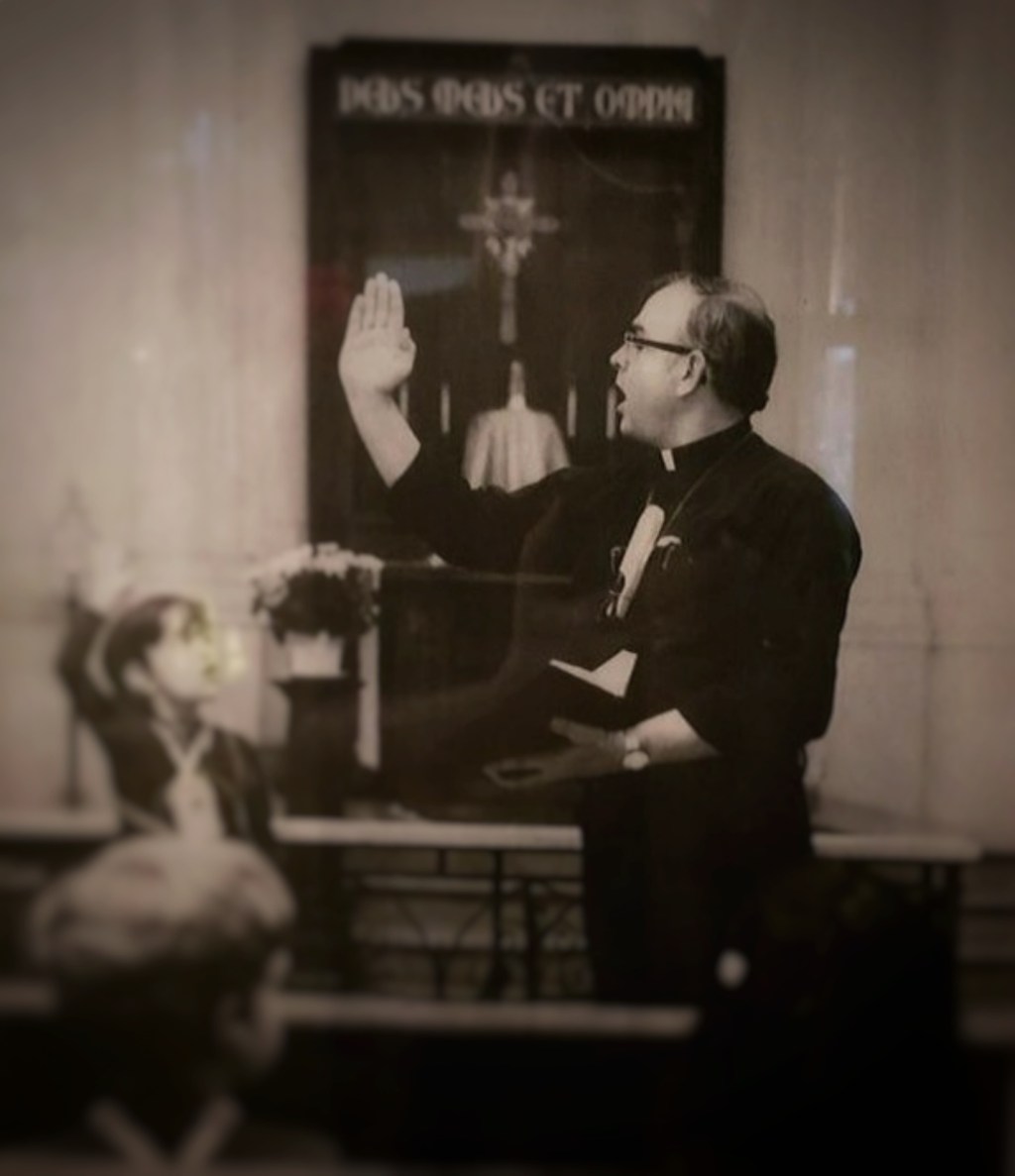

-

By Sarah E. Murphy Many of the names on this long overdue list of 75 priests credibly accused of sex abuse, finally released by the Fall River Diocese on January 7, are no surprise to me, but they’re a sad validation of the work I’ve been quietly doing for the past three years. “Father Bill”…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy School night snowstorms were the highlight of those long, dark winters. Dad was a misguided meteorologist with only the best intentions. When he professed “there’ll be no school tomorrow!” with cheerful certainty we could plan on the screech and halt of the bus flying down Grand Ave so we learned early…

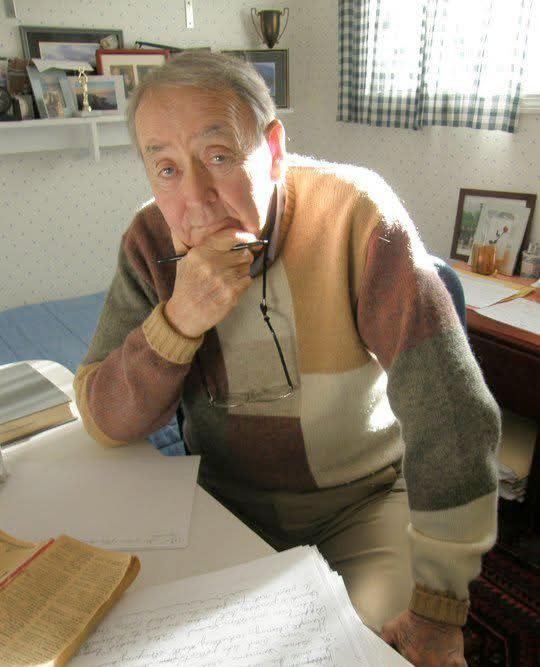

-

By James F. Murphy Jr. (1932-2015) Intro by Sarah E. Murphy Write what you know. It’s what my father always told his students, but I always reiterated to him, for I believe his best writing is autobiographical. His words had an elegant cadence, full of rich description and poetic alliteration, no matter the subject. He…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy In 2020 America, we’re celebrating a century of women’s suffrage while simultaneously defending a woman’s right to govern her body. The Margaret Atwood allusions became tired long ago. Throughout this election cycle, women and their families have also been forced to defend the most difficult medical and emotional decision imaginable –…

-

Text and Photos by Sarah E. Murphy The life of Chase R. Soares ended far too soon, but his family is making certain that his legacy lives forever. Since Chase’s tragic passing at the age of 23 last February, his mother, Brooke Lopes DeBarros has navigated her grief by focusing on the bright light her…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy David O’Regan used to hide from his past. Facing it has become part of his healing. David and I connected on Facebook in the summer of 2019, and although we’ve never met in person, I consider myself lucky to call him a friend. I always look forward to his thoughtful posts,…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy A colorful call to action illustrating the importance of voting will be on display at Falmouth’s Peg Noonan Park on Main Street through Election Day. The project was spearheaded by the Falmouth League of Women Voters, which hosted a community painting day on Saturday, October 10. Conceived by Falmouth resident Sarah…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy It seems impossible my father has been gone five years. Since I watched “It’s A Wonderful Life,” or willingly listened to Celtic music. Since he enveloped me in the comforting scent of after shave, soap, and wool. Since I went from being a Daddy’s Girl to a Fatherless Daughter. Dad never…

-

Text and Photos by Sarah E. Murphy Jeff should be turning 50 today. I know there’s a raucous party going on in Heaven, but selfishly, I think he should be here with us, ringing in his milestone birthday with a guitar solo, while his On The Rocks groupies raise our glasses during Friday Night “6…

-

Text and photos by Sarah E. Murphy There are two things fundamental to my upbringing that have been missing from my life for the past twenty years – a dog and an outdoor shower. My husband and I are currently all set with pets, since our 15-year-old cat keeps us up all night, every night,…

-

By William Verdad Intro by Sarah E. Murphy It was February 2019, and I was packing for my first trip to Rome, when I received a Facebook message from a friend thanking me for an article I had just written about clergy sex abuse. In it I shared the story of a man in my…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy As small, suburban flowers we were replanted in more nourishing, salty soil and the ocean soon became the backdrop of our lives. It roared to us on ghostly winter nights while we burrowed in tiny beds assuring us we’d soon return. And so we did. For at the close of each…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy I recently visited my brother T.M. Murphy’s Monday morning session of The Just Write It Class in Falmouth Heights. Thankfully Covid-19 hasn’t cancelled the 2020 season of this long-standing summer tradition, now in its 25th year. Since he first started teaching in The Writers’ Shack, Ted has encouraged kids to follow…

-

By James F. Murphy Jr. *Copyright 1993. Reprinted in “Chicken Soup for the Veteran’s Soul,” 2001. My most vivid memory associated with the American flag flashes to Korea and a gray, clammy day in early August 1953. The Korean War had come to an end a week earlier, on July 27 at precisely 10 PM.…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy The Fourth of July is now a memory, and my husband and I have been in quarantine since before St. Patrick’s Day. While we’ve slowly but surely been getting out a bit more as the months creep by, the global pandemic persists. As I write this, it’s a flawless summer day,…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy The Island Queen is making waves and taking strides to promote clean waters with the purchase and installation of the “Seabin,” Cape Cod’s very first floating trash bin. The device is part of a global initiative founded in Australia by two avid water lovers committed to reducing trash with the end…

-

By Sarah E. Murphy Life couldn’t be more different now than when I last wrote. In January of 2020, the year held much promise, and despite all that has transpired since, I still believe that. The onset of the global pandemic almost seems like a distant memory here in the United States, for those on…

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.