By James F. Murphy Jr.

The following article, written by my late father, was originally published in The Boston Globe Travel section on December 3, 1995.

Much like Ishmael in “Moby-Dick,” I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is damp, drizzly November in my soul, I head for Ireland.

Ireland? At this time of year?

Usually the cold blasts of winter nudge my Cape Cod neighbors south to Florida, but for the last several winters some mystical urge has sent me to the home of my ancestors: Dublin, Cork, Galway.

I have found Ireland in the dead of winter to have all the charm most lovers of Ireland revere for verdant hillsides, placid lakes, and singing pubs in the west of Ireland during July and August.

Ireland hops, skips, and dances in the “dead” months. The real Irish emerge, and the pace, certainly slower than most tourist spots by the very nature and culture of the places, slows to a crawl in winter. It is a time for “the chat.” Conversation, never rushed, becomes lyrical and poetic. There is time to appreciate the language and its flow, and the weather, contrary to popular opinion, is generally sweater-cool, comfortable, and soft.

When a resident asks me if I am alone and I answer, “Yes,” I hear, “Ah, a shame. Two shorten the road.”

Other expressions of rural and poetic philosophy not dependent on long, summer nights and golden days: “The beginning and end of one’s life is to draw closer to the fire”; “Praise the young and they will blossom”; “The well-fed does not understand the lean”; “The windy day is not for thatching”; “Put silk on a goat and it is still a goat”; and in the Gaelic, “Is ceirin do gach creacht an hoighne.”

“Patience is a poultice for all wounds.”

In this casual season of the year, it is possible to strike up long conversations with priests, poets, politicians, farmers, barmen, children, and the elderly. Ireland is a nation of conversationalists. I have heard barmen, beer salesmen, dustmen, and carpenters give their critique of an Abbey play with the same erudition and feel for the theater that a professional critic might offer.

Winter, too, is the best time to get to know, or at least observe, many of the colorful characters. And speaking of them, in recent years, Dublin has seen the passing of Christy Brown, “Bang, Bang” and “Johnny Forty Coats.” Christy is familiar from the film, “My Left Foot,” but the other two may not be easily recognizable.

“Bang, Bang” is an avid devotee of the Old West, would ride the Dublin double-decker buses, point his two fingers at passersby and shout, “Bang, bang, gotcha.” Many gracious Dubliners (police included) would clutch at their hearts and “die” for old “Bang, Bang.”

“Johnny Forty Coats,” fearful of the demons of the past, draped, cloaked, and covered himself with as many layers of clothing as he could find to ward off the cold of his childhood as he lumbered and wrestled under his woolen burden along O’Connell Street – even on the warmest day in July.

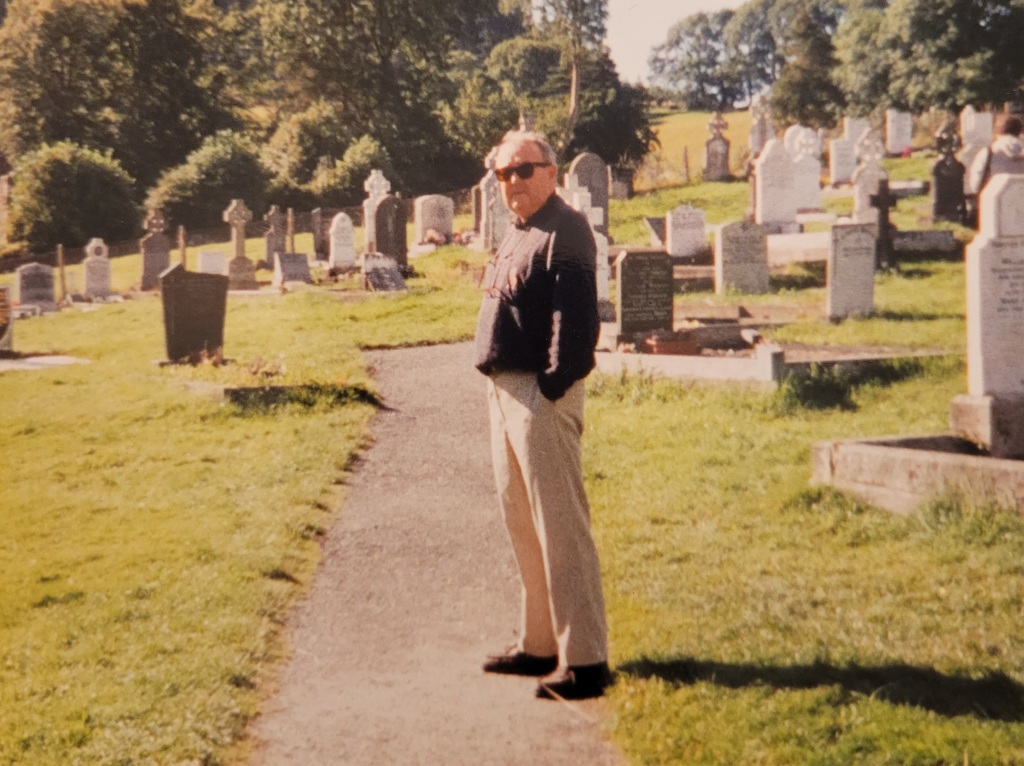

Brendan Behan, buried in historic Glasnevin Cemetery, his voice silent now but his prose forever riotous and bawdy, is almost lost in a grave surrounded by gnarled and hostile trees. With the help of my taxi driver and a Glasnevin gravedigger who quoted, narrated, and lectured on the works of dear Brendan, I found the playwright’s final resting place. I doubt I would have been given such special attention in the hurly-burly of the summer tourist season.

The old characters are gone, but there will always be colorful characters in Dublin, and “Johnny One Drink” is one of them. Dressed meticulously, red boutonniere in his lapel, he walks ceremoniously into his favorite pub every Saturday at half-eleven (that’s 11:30), orders a large whiskey, adds five ounces of waters, sips, swallows off the remainder under the careful scrutiny of the rest of the bar crowd and nods his goodbye to the bar man.

“Where is he going now?” I ask.

“Shopping with the Mrs.” is the response.

“Is that it? Will he have another drink?”

“No, that will be it,” says the longtime friend. “That will be it, until half-eleven next Saturday.”

Others at the bar shake their heads.

“We could all do with a bit of discipline,” says one.

“Aye,” the others join in. “We could that.”

And there are other characters, but not all citizens of the Republic. A few weeks ago, I was walking across O’Connell Bridge with a professor friend from Dublin City University. Framed before me for all of Ireland to see was an apparition that seemed to appear from nowhere.

There were two of them. They were in green. No, that is incorrect. They were green.

From the green scally caps all the way down to bright, verdant running shoes, they competed most successfully with all the Jolly Green Giants of this world.

I turned to my friend and said, “Peter, did you see that study in green?”

“Yanks with the wrong idea,” he replied. “The wearing of the green is inside, Jimmy. It’s not how you dress. It’s how you be.”

But on to more practical aspects of Ireland in winter.

The Talbot Guest House on Talbot Street was about $45 for a single, $65 for a double, and $115 for a suite. All rates quoted are per room, not per person. The Talbot is less than 500 yards from the Abbey Theatre and one block from O’Connell Street. The Irish pound, or punt, was worth $1.61 US at this writing.

Tickets to the Abbey are reasonably priced between $15 and $25 and never sold out in winter.

Prices all over the country drop dramatically in winter. When I took the train to Cork City, round trip was a little more than $35.

Speaking of Cork, one of the unique experiences I had was my visit to the Cork City Gaol in Sunday’s Well. While visiting a jail may not appeal to most tourists, to an Irish-American it expresses that other aspect of our duality – melancholia. The prison housed “criminals” in the 19th century under deplorable and inhumane conditions. Many confined there had committed the heinous crime of stealing bread and a landlord’s potatoes to feed a starving family.

The cells are furnished as they were in those oppressed years with lifelike characters and sound effects of clanking doors and hellish screams of pain, both emotional and physical. The effect is chilling. Guided tours are arranged upon request but, again, because of winter and a less hectic tourist season, I was able on my own to browse, to think, to reflect on man’s inhumanity to man.

When I departed, I felt better for having visited and vicariously experienced the injustices of that 19th-century world. I was grateful, also, to my grandparents for braving stormy seas and settling in Boston.

Admission prices to Cork Gaol are about $4.50 for adults, $2.50 for children, $3 for students, and $11 for a family ticket.

Of all the winter values, the Blarney Park Hotel in the village of Blarney – and just a blown kiss to the Blarney Stone itself – is one of the great buys in Ireland.

Midweek prices of about $60 for a room and full Irish breakfast and dinner, or three-night weekend stays for a little less than $100 – with saunas, heated pool, intimate pub, and quiet saloon with crackling fires. And the Blarney Woolen Mills is just a two-minute walk away.

For more information, write to Gerry O’Conor c/o the Blarney Park Hotel, County Cork, Ireland; or phone 021-385281, telex 75022 or fax 021-381506.

Ireland of the Welcomes awaits you all the seasons of the year, but becomes a little less lonely in the winter and would like to have a relaxed chat with her American friends.

James F. Murphy Jr., a Falmouth novelist, is an associate professor at Massachusetts Maritime Academy and a visiting professor of writing and literature at Boston College.

Happy St. Patrick’s Day, Daddy.

Leave a comment