By James F. Murphy Jr. (1932-2015)

Intro by Sarah E. Murphy

Write what you know. It’s what my father always told his students, but I always reiterated to him, for I believe his best writing is autobiographical. His words had an elegant cadence, full of rich description and poetic alliteration, no matter the subject. He wrote the following essay in the summer of 2008, after watching Barack Obama address a diverse and jubilant crowd in St. Paul, Minnesota, when he became the presumptive nominee of the Democratic party, and the first African-American to do so.

My father was overcome with emotion, for many reasons, and penned the following reflection, which I typed for him and submitted to the Cape Cod Times for consideration; it was published later that summer.

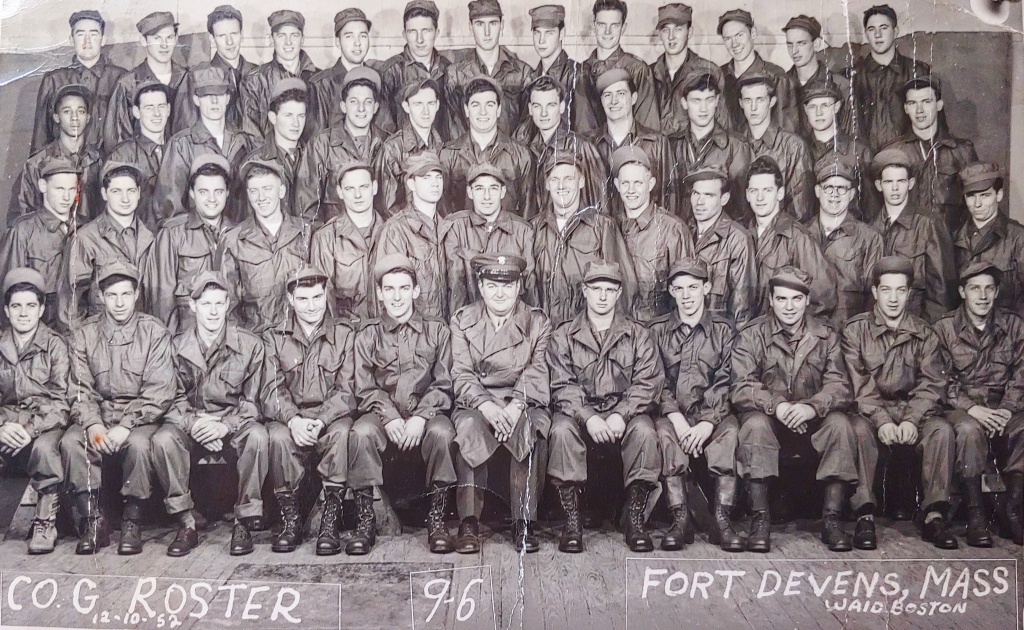

My father is pictured first from the left in the top row, at age 20, at basic training. He didn’t meet his friend, Nickie, whom he honors in this essay, until he was in Korea, and he never forgot him. Over the years, my dad and I tried to find Nickie, but we didn’t have much to go on. I searched the web and followed-up on a few leads, with no luck.

There are so many times I’ve pondered my dad’s words – while watching Colin Kaepernick kneel in peaceful protest, while holding a sign and waving to my fellow Cape Codders to respectfully demand racial justice, or while watching Spike Lee’s fictional account of the very real experience of the African-American soldier in his riveting film, “Da 5 Bloods.”

This morning, I thought of my father and Mr. Nickie, and how grateful they would be to see their sacrifices being respectfully honored by President-Elect Joseph Biden and his wife, First Lady-Elect Dr. Jill Biden at Philadelphia’s Korean War Memorial. And how jubilant they would be to see the United States has finally joined the more evolved and sophisticated countries around the globe by finally sending a woman to the White House – one of Jamaican and Indian descent.

On this Veterans Day, I send my deepest gratitude to all who have fought for our freedom, but especially the heroes who have been forgotten, overlooked, and taken for granted because of their skin color.

This is for you…

A Sort of Homecoming: Unsung Heroes of the Forgotten War

By James Francis Murphy Jr.

Recently, as I watched Barack Obama speaking to an audience of people from all walks of life, my thoughts traveled back over 50 years to a troop train and a five-day trip from Fort Lawton, Washington to New York City.

We soldiers on board were returning from service in Korea and we settled in comfortably, “compliments” of the United States Government. My friend, Nickie, an African-American, referred to as a “Negro” in those days, took the top bunk and I took the lower.

“I like it up here, Jimbo. I feel like Jimmy Cagney in White Heat. ‘Top of the world!’” he said, followed by a pretty good Cagney impersonation.

I responded with my best Walter Brennan, and we began five days of laughing and sharing our impersonations of movie stars.

We had met in a field hospital, where Nickie was receiving treatment for wounds he had suffered earlier when on night patrol and, I, less dramatically, was there recuperating from a bout with malaria.

We hit it off immediately, but after our release from the hospital, we lost touch with one another until we met at a staging area in Fort Lawton, just a few days before we embarked on the journey home. Despite the passing of time, we picked up where we had left off.

Once on board, Fred, the African-American porter, took good care of us, along with the eight other soldiers in his assigned station. As he sat on the edge of my bunk, Fred regaled us with stories of his years as a Pullman porter, while Nickie listened intently from his perch above.

Fred mentioned a name I have never forgotten, Mr. A. Phillip Randolph. “Yes, sir. He is my hero, and a hero of all the Georges.” Fred nodded.

“Georges?” I asked.

He smiled. “All the porters are called “Georges” because of George Pullman, the founder and owner of the Pullman Company. And Mr. Randolph is our hero because he fought to unionize us. He certainly improved our lives.”

“Should we call you George?” Nickie laughed.

“No, call me Mr. Fred and I’ll call you Mr. Nickie and Mr. Jim. Is that okay with you?”

Throughout the following days, Nickie and I caught up on our meeting in the hospital, and the laughs we had shared. We would stand out on the iron platform between the two cars and swap stories of sergeants we knew and loved and, well, the others.

As we talked, the lurching train twisted through the narrow corridors of the Dakotas, past valleys and lofty mountains, brushed alongside the green rows of Wisconsin farms that stretched for acres, and on toward the cattle of Nebraska that grazed in the sweet sweep of grassland.

“Boy, it really is a big country, Nickie,” I marveled.

“Sure is,” he sighed. “Sure is.”

One night, as we stood on the platform, with the scent of apple and berry orchards and the pinch of pine in the air, Nickie seemed alone in his thoughts, even though I was at arm’s length. For some reason, I was mature enough to linger quietly as the clattering and rattling of the tracks below seemed to accentuate what was unsaid but palpable.

Finally, he turned to me. “You know, Jimbo, I don’t think I’ll ever play baseball again. I was a damn good pitcher. But, that shrapnel tore a lot from that shoulder. I’ll miss baseball. But, I suppose a guy can’t play a game for the rest of his life,” he joked.

“Nickie, I read somewhere they can do wonders these days with wounds and injuries,” I pronounced with the naïve confidence of a 21-year-old.

“Yeah, we’ll see. Hey, maybe I’ll come visit you and we can go see Ted Williams and the Red Sox.”

The stories of the war, baseball, girlfriends, and movies passed too quickly as we raced East and then quite suddenly, we were pulling into New York and Penn Station on the morning of August 10th. We looked out the windows of our bunks, and instead of the vast prairies we had left behind, we craned our necks at the towering buildings of Manhattan.

“It’s over, Nickie,” I yelled up to him. “We’re in New York City.”

“Yeah, we are. It’s been a great ride, Jimbo.”

Later, as I stood in front of a full-length mirror in an antechamber outside the men’s room combing my hair, Mr. Fred stepped in.

“Well, now, look at Mr. Jim getting all gussied up to meet the ladies.” And then suddenly, his tone became serious. “I wouldn’t go into the men’s room if I were you, Mr. Jim,” he warned.

“Why not?” I asked.

“Because Mr. Nickie is in there.”

“I don’t get it. What difference does that make?”

“He’s crying.”

“He’s crying? Why is he crying? We’re going home.”

“Where do you live, Mr. Jim?”

“You know where I live. Outside of Boston.”

“Mr. Nickie lives in Mississippi.” He shook his head and left.

In the excitement that poured out of us like a river, we grabbed our bags and headed for the buses to take us to Camp Kilmer in New Jersey to be discharged from the Army. I never saw Nickie again and I didn’t even have his address.

So the other evening as I watched Barack Obama, a five-day journey that took place over half a century ago came flashing back, almost as if it were yesterday, and I thought of my friend.

I found it difficult to keep the tears back as Barack Obama, the first African-American presidential nominee, spoke before a stadium of supporters. I hoped that somewhere, Nickie was watching, his eyes moist and hopeful, and I thought, ‘Top of the world, dear friend. You have finally come home.’

Photo by Sarah E. Murphy

Leave a comment