By Sarah E. Murphy

The first time I ever heard about my great-aunt Margaret Matthews, I assumed she was the namesake of my mother, Margaret Ann, the only girl in a family of three boys.

“Oh no,” my mom said, when I asked her one day while staring at Margaret’s photo. “I was named for Margaret Shea, my mother’s sister, from PEI.”

I didn’t understand why she couldn’t be named for both since Margaret Matthews was my grandfather’s sister. Didn’t he have any input on the name of his daughter? I was aware even as a child that Nana Matthews had been the decision-maker in her family and, subsequently ours, but didn’t Papa think of his own beloved sister every time he spoke his daughter’s name? Didn’t he turn his head to look for her whenever someone addressed my mother?

Aunt Margaret has essentially been forgotten from our family history. Now I understand why.

Margaret died of tuberculosis in 1930, five years before my mother was born. She was thirty years old.

Growing up, I had only heard about my grandfather’s four sisters, “the Aunts,” Anna, Lil, Sal, and Marion, so I never quite made the connection between the woman in the black and white portrait and the rest of the family for she seemed more like a distant figure from the past.

But this was our past.

Aunt Margaret is buried in the Matthews family plot in Calvary Cemetery in Waltham, a few miles from where she grew up in Newton and lived until her death. I visited the Murphy and Matthews family graves with my parents as a child, but back then, Aunt Margaret was just a name on a stone – Margaret H. Gately – down at the bottom of the list of names. But she still didn’t really seem like a member of my family.

Last winter, my husband, Chris and I stood before her grave with my Uncle Jackie, my mother’s youngest brother, following a post holiday lunch at Fiorella’s, a cozy Italian restaurant he loves, which happens to overlook the graveyard. When I realized where we were, I asked if he wouldn’t mind making a quick visit, along with a drive-by tour of some of the former Matthews family homes.

Staring at the tombstone, I was overcome with sadness, wishing there were people who could answer my questions.

How did Margaret contract the disease? Where did she spend her final days? Did she die at home? Was she alone? Was she scared? What became of her husband? Was he loving? Was he by her side in her final moments? By all accounts, my family had no further contact with my great-uncle.

I also can’t help but feel anger, thinking of the unnecessary shame and isolation my great-aunt endured while fighting for her life, knowing all the milestones she’d never experience. I have tremendous sympathy for her family, her immigrant parents forced to bury an adult child, who coped the only way they knew how, by simply moving on with life, never speaking of her, as if she didn’t exist. Back then, people didn’t have the luxury of grieving, and my family was also trying to hide a shameful secret. Tuberculosis was a “dirty” disease that had long been associated with the Irish, and by the time Margaret died in 1930, it had become far less prevalent, only adding to the shame.

I’ve been thinking of Margaret constantly throughout this election in which the degradation of basic human decency has become acceptable since our political landscape took a drastic turn in 2016. The Land of the Free and the Brave has returned to a place of unapologetic ethnic and religious division and scapegoating. These tactics are nothing new, evidenced in the days of Yellow Journalism, but now they are perpetuated and manipulated by technology, social media, AI, and media more concerned with clickbait than democracy.

When I hear the Republican Presidential and Vice-Presidential nominee spewing lies and conspiracy theories, garbage designed to dehumanize Haitians, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and other ethnic and religious groups, while everyday Americans parrot their filth, I think of my immigrant family, the power of ignorance, and how easily people fall prey to prejudice when stoked by fear. Many of the stereotypes against the “Fighting Irish” remain to this day and are embedded in our culture.

When my childhood home in Falmouth Heights was bustling with family and activity, Margaret’s picture was quietly in the background, displayed on the white bookcase in the family room. Fittingly, on the shelf where my parents displayed a portion of their immense collection of Irish history, including the Emigration Story. My family’s history and that of so many Irish-Americans is weighed down with the baggage of generational trauma. Shame – a control tactic of the Catholic Church and the English, reinforced upon arrival with the greeting, “No Irish Need Apply.” Workaholism in an attempt to overcome the shame, acquire property, and establish roots, all to prove worth. Alcoholism as a form of self-medicating to numb the pain from shame and the grief of being displaced from homeland and loved ones, many of whom never returned. For my ancestors, a “better life” in America meant saying goodbye to the only one they knew. These are just some of the traits of the emotional inheritance passed down like the family farm through generations.

Margaret is a kindred spirit, for I could have just as easily become a footnote in our family history, and in many ways, I did. For 25 years, I tried to blend in and disappear, living in fear of my “dirty” secret being discovered and revealed. In 1995, when a drugstore test at age 23 confirmed what my body already told me – that I was facing an unplanned pregnancy – my very first thought was the shame I would bring upon my family. The shame I’d already brought.

My second thought was harming myself because I believed they’d be better off without me.

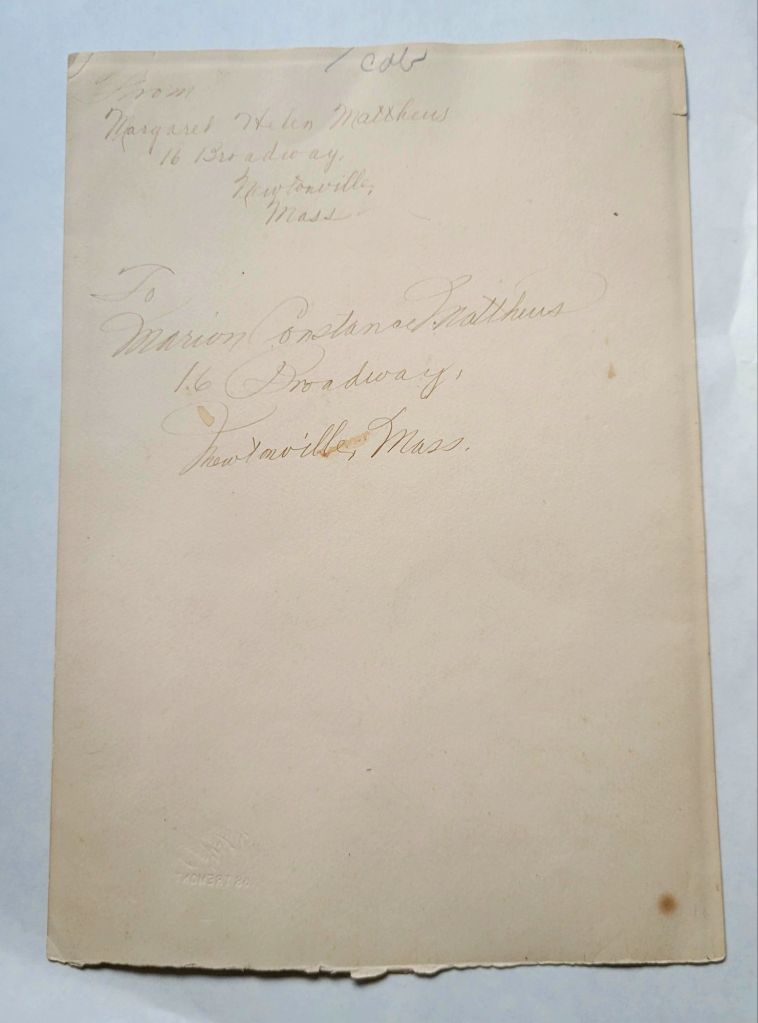

All those times I stared at Aunt Margaret’s picture, I never noticed the inscription until it was removed from the frame many years later. As a child, I thought she was a grown woman, but it’s most likely her graduation photo, which she personalized to her youngest sister, who was four years younger, in September 1919.

“To my sister, Marion, in honor of the fights we had.”

The normality of it brings me to tears. Sibling rivalry and private jokes. A regular teenage girl, no different than I once was.

On the back is the address of their family home, 16 Broadway Street, once bustling with people like mine at 36 Grand Ave.

People have always told me I look like my mother, and my husband sees a resemblance between Aunt Margaret and me.

As the election looms closer, I look around at a nation I currently don’t recognize, which is why I’ll never be complacent, and I’ll always demand the best from my country. I refuse to allow my family’s American dream to be shattered. I’ve felt like an outsider in my own country for so long, I now feel like an immigrant. But instead of shame, it brings me pride. I’ll never forget my roots.

Leave a reply to Maureen Garrity Cancel reply